The history of Clashmore Distillery is a brief but colourful one and indeed this establishment stood alone in this county for the best part of 175 years until the recently established Blackwater Distillery produced its first distillate back in 2015.

One might easily wonder how it came to be that a distillery of such scale would come to be established in a small village like  Clashmore, but for the answer to that question, one has to remember that this area was in the midst of its own 'industrial revolution' in the late 18th/early 19th century. On the site of the distillery itself was a long-established Boulting Mill run by the same Lawrence Dennehy who later would become the Master Distiller - he was recorded as being a 'Cornfactor' as early as 1807, that is a corn merchant, and having ownership of Clashmore Flour Mills and Millhouse, so it is safe to presume the Mill enterprise was already running before this time. Also in the early 19th century the village and surrounding areas abounded with other industrial enterprises such as the Flour Mill at Glenlickey, a limestone quarry at Laurentum, the Slate Quarries at Knockbrack and across the Lickey at Kilgabriel and later even a Flax Mill which was run on the Huntingdon Estate. Clashmore, but for the answer to that question, one has to remember that this area was in the midst of its own 'industrial revolution' in the late 18th/early 19th century. On the site of the distillery itself was a long-established Boulting Mill run by the same Lawrence Dennehy who later would become the Master Distiller - he was recorded as being a 'Cornfactor' as early as 1807, that is a corn merchant, and having ownership of Clashmore Flour Mills and Millhouse, so it is safe to presume the Mill enterprise was already running before this time. Also in the early 19th century the village and surrounding areas abounded with other industrial enterprises such as the Flour Mill at Glenlickey, a limestone quarry at Laurentum, the Slate Quarries at Knockbrack and across the Lickey at Kilgabriel and later even a Flax Mill which was run on the Huntingdon Estate.

Also a major factor was the fact that a vital piece of legislation had just been passed in 1823 called the Excise Act which made it easier for prospective distillers to establish themselves when it introduced a fixed licence fee of £10 and reduced the excise duty level to a payment per gallon distilled of two shillings and five pence per gallon which is about 12p in todays money. Many other distilleries opened during this period on the back of this and indeed Midleton Distillery was established in the same year by the Murphy family.

Establishment

It was against this backdrop that Clashmore Distillery was established in March 1825 by Lawrence Dennehy of Laurentum House and Robert Power Ronayne of D'Loughtane House, both affluent and prominent businessmen of the parish. This milestone was recorded in the printed press at the time where it was stated that "the above establishment is now at full work, under the supervision of a long-experienced and scientific distiller; which aided by the vast fall of water, and other peculiar advantageous circumstances enables them to offer at least as good an article for sale, as can be done by any in the trade, and at as low a price…any orders they are favoured with shall be promptly attended to…"

The excise returns for the full year to October 10th, 1826 show that Clashmore Distillery had produced 27,288 Gallons of spirit, from 205,584 gallons of wash and a similar number of 24,971 Gallons of spirits during the year following, having used 2,254 bushels of malt in the making. A bushel was an imperial unit of measuring dry goods, such as grains and was the equivalent of 8 gallons. So it is fair to say that the distillery output in those initial years was substantial.

Distillery Operations

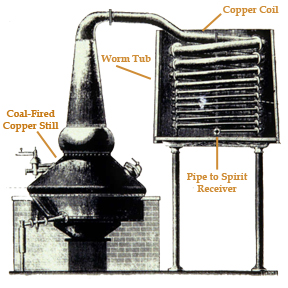

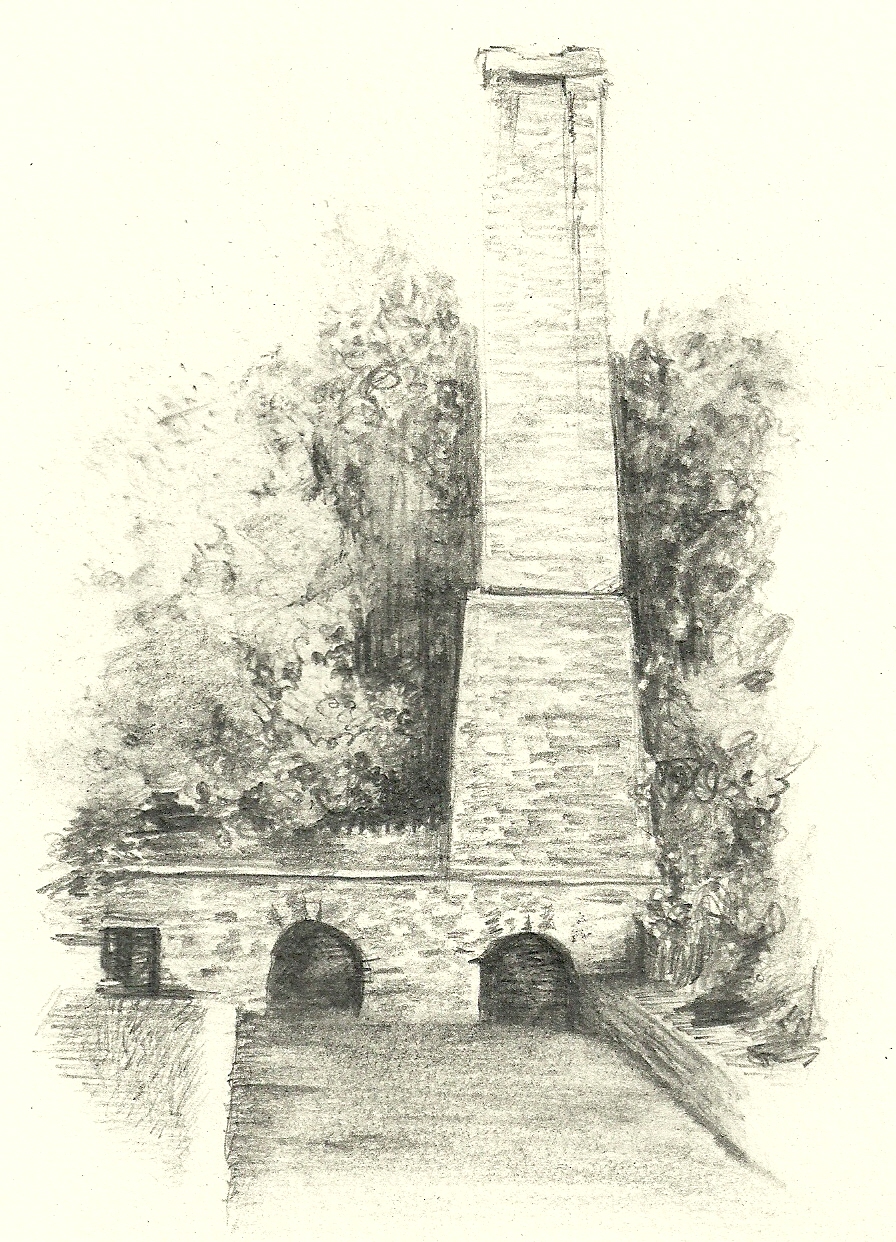

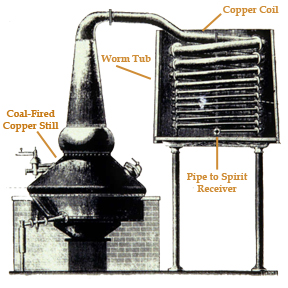

It is hard to fully envisage the internal machinations of the distillery, but some detail does exist about the equipment which was used and crucially it is known that the mill/distillery was being fed from a mill ‘race' or stream which was culverted off the Graigue  River several hundred metres upstream just south of O'Riordan's farm buildings as they are today. In all, this ‘watercourse' had a substantial fall of 14 feet and eventually crossed the road under a shallow bridge at what was the old forge at the time. It then ran due south along the back wall of the mill buildings where it fed the worm tub and coppers which needed a constant supply of cold water and at one point drove two metal water wheels which presumably served both enterprises i.e. the internal machinery of the distillery such as the pumps and the millstones within the flour mill. It is a testament to the fall of water here if it was utilized to supply both the distillery and flour mill adjacent to each other, but it is not clear if both operations ran in parallel during this period. The distillery chimney itself presumably served the furnaces which heated the stills but also possibly doubled as a mechanism for drying the malted barley which was employed within some distilleries. Distribution of the finished product was relatively straight-forward for the distillery as the casks merely had to be transported by horse and dray to nearby Raheen Quay where they would be loaded on to a waiting ‘lighter' by the ‘lightermen' (a lighter was a type of barge for carrying goods) and brought to the nearby port of Youghal for shipping. In return the lighters would bring in much of the raw barley product for use in the distillery, along with coal, timber and many other supplies for the retailers of the village. River several hundred metres upstream just south of O'Riordan's farm buildings as they are today. In all, this ‘watercourse' had a substantial fall of 14 feet and eventually crossed the road under a shallow bridge at what was the old forge at the time. It then ran due south along the back wall of the mill buildings where it fed the worm tub and coppers which needed a constant supply of cold water and at one point drove two metal water wheels which presumably served both enterprises i.e. the internal machinery of the distillery such as the pumps and the millstones within the flour mill. It is a testament to the fall of water here if it was utilized to supply both the distillery and flour mill adjacent to each other, but it is not clear if both operations ran in parallel during this period. The distillery chimney itself presumably served the furnaces which heated the stills but also possibly doubled as a mechanism for drying the malted barley which was employed within some distilleries. Distribution of the finished product was relatively straight-forward for the distillery as the casks merely had to be transported by horse and dray to nearby Raheen Quay where they would be loaded on to a waiting ‘lighter' by the ‘lightermen' (a lighter was a type of barge for carrying goods) and brought to the nearby port of Youghal for shipping. In return the lighters would bring in much of the raw barley product for use in the distillery, along with coal, timber and many other supplies for the retailers of the village.

As for the men involved in running the distillery operation itself, several skilled operatives might typically have been required in an operation like this, such as a Maltster, who was someone who prepared the barley/malt for distilling purposes and the Distiller himself, who of course managed the entire distillation process from end-to-end. Also some Excise Officers of the Crown would have been attached to the distillery, namely a Charge Officer, who was a Mr. Bold for a time, and who was employed to visit the distillery every four hours of the day and prove and measure the spirit being produced – he most likely would have had a residence on or close to the premises. The Charge Officer was the only one with a key to the padlock on the Spirit Receiver, which was supposed to be the only place where spirits could be drawn off. Above him was a Supervisor of Excise whose duty it was to visit occasionally and keep tabs on the Charge Officers in his district – up to 1828 this role was filled by a Thomas Sargent Esq, followed by a William Parker Esq in 1829 and later by a Mr. Kearnan. The distillery also would have needed a guard who should not allow anyone in or out of the premises unless they had a ‘pass' from the Charge Officer – this is how closely regimented premises of this nature were at the time.At least as early as 1827 Lawrence Dennehy was attempting to sell or lease the distillery which may have been the plan from its establishment and as early as 1829 it appeared to be under the control of his son John Dennehy, as he is recorded in later years as having the main stewardship.

Local Anecdotes

Of course some famed stories and legends are attached to this distillery, one of which maintains that the distillery had a secret cellar nearby where much of the spirit produced was hidden to avoid paying excise duty on it. This was reputed to be located in Robert McCarthy's house in the village who ran a public license himself (next to the present John Power's and a house which no longer exists) - there is no great surprise in this tale as this establishment and many others like it went to great lengths to avoid paying some of the excise duty owed to the Crown and indeed the excise officers were often led a merry dance when they made their routine calls! Another legend associated with the distillery is a well-known one whereby ahead of an impending raid by the excise officers, that the workers had no choice but to dump thousands of gallons of spirit into the River Graigue, which led to reports that the cattle further downstream who were drinking at the river were seen staggering around drunk later that day!

Controversy

Records on the distillery are scarce for the early 1830's, so its story can be picked up again in 1834 when the whole operation was shrouded in controversy due to another incident with the Crown's excise officers, which eventually came before the Court of Exchequer in February 1834. The charge against John Dennehy was that he had a receiver, called a spirit receiver, in which there was a certain hole, not authorized by law, by which he had incurred the penalty of two hundred pounds (this was the equivalent of approx. £125,000 in today's money and the fine was later disputed by Dennehy at this court. The case had arisen from the fact an inspection was made on April 24 th 1833 by the Surveyor General Examiner John Knapton and another General Examiner Jonathan Barber of Mr. Dennehy's distillery and they found an illegal hole under the spirit receiver which they afterwards attested could have been used to draw off spirits without the knowledge of the revenue officers and hence any duties payable to the crown could be indefinitely evaded. An aggravating factor in this case was the fact the distiller had a father and a cousin in the retail trade in Clashmore Village – a distiller himself was not allowed to be a spirit retailer but nothing barred friends or family members from being such and of course this may have been an outlet for any illegally held whiskey.

A very detailed account of the case was recorded in the Freeman's Journal at the time, but after much postering, the prosecution case could not produce enough evidence that any such incriminating syphon was present on the day of inspection and thus the jury had no other choice but to rule for the defendant Dennehy and the hefty fine was dismissed.

Dwindling Fortunes

After this time, the fortunes of the distillery seemed to dwindle and it passed through a few different hands before eventually ceasing to operate. By the end of 1835, John Dennehy made another push to sell or lease the Distillery property, along with the Mills, Malt House, Stores, a Dwelling House and about 20 Acres of land.

And indeed by October 17 th 1836, the distillery was in full operation again under the stewardship of brothers Robert and Edward Dower from Dungarvan who, after their father Robert, were part of the brewing legacy at Fair Lane, Dungarvan which of course later become the renowned Power's Brewery. When they began distilling it was stated publicly that “from the very great improvements made in every department of it, that they feel confident they will be enabled to offer as good an article as any in the trade, it being under the superintendence of a scientific and efficient distiller – the highest price will be given for Oats and Barley.” It is interesting that the distillers were also seeking Oats as well as Barley, but it was not unknown for some Pot Still Irish Whiskey of the time to use some Oats in the mash as it was reported to render it more workable. It can be seen from the excise returns for the year 1836 that approx. 37,500 gallons of spirit were produced so quite an increase in output from previous operations. The Dower brothers had made quite an investment in the operation as it was reported later that £4,000 had been spent on renewing and adding new equipment (this is the equivalent of £2.5 million in today's money!). But this level of investment soon came back to haunt them as within 12 months the two Dowers were before the Court of Bankruptcy at the Four Courts, Dublin and the distillery was put up for sale or lease again.

Final Days

After this time the premises was leased by a John O'Keeffe of Crosses-Green Distillery, Cork City and controversy again reared its head in 1839 when the Dennehys, Lawrence and John and partner Robert Ronayne took an action against John O'Keeffe for illegally removing to Cork a part of a still which had been installed by the previous tenant Mr. Dower. The City Court returned a verdict for the plaintiffs and called for damages of £5 to be paid to the Clashmore men. It can only be presumed from the details of this action that the Dennehys and Ronayne still held the majority ownership of the premises at this stage and that previous actions taken by the Court of Bankruptcy against the Dowers eventually led to the ownership either defaulting to the original owners or else being sold back to them by another arrangement. Later attempts were made to lease or sell the distillery on again but no records exist after this time so the history trail ends here and hence it is taken that by 1840 the distillery had ceased to operate.

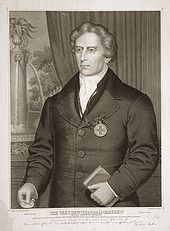

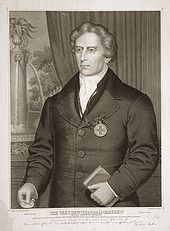

One of the major factors behind the demise of this operation and others like it was thought to be the advent of the ‘temperance movement' pioneered by the renowned Fr. Mathew in 1838 which was said to have severely damaged the prosperity of the distilling  industry and the income of barley growers, especially in Cork and neighbouring counties where the ‘total abstinence' movement was centered. In the decade following the start of the temperance campaign in 1838, the number of bushels of malt upon which the required duty was paid fell by about 25% and crucially in the same period the consumption of grain spirits in Ireland had declined by about 50% which likely had a detrimental effect on the industry locally. There is strong evidence of the influence of the ‘temperance movement' in Clashmore and West Waterford in general and indeed Fr Mathew visited the village himself in 1842 to administer the abstinence ‘pledge' upon the gathered masses. Couple this with the fact that previously a well-known ‘second apostle' of this movement, Rev. John Foley, who was a Catholic Curate in Youghal but hailed from Clashmore itself, had already exerted his considerable influence on the ‘unemancipated' masses of Clashmore village itself and the surrounding areas in an attempt to free them from the scourge of the ‘grain'. industry and the income of barley growers, especially in Cork and neighbouring counties where the ‘total abstinence' movement was centered. In the decade following the start of the temperance campaign in 1838, the number of bushels of malt upon which the required duty was paid fell by about 25% and crucially in the same period the consumption of grain spirits in Ireland had declined by about 50% which likely had a detrimental effect on the industry locally. There is strong evidence of the influence of the ‘temperance movement' in Clashmore and West Waterford in general and indeed Fr Mathew visited the village himself in 1842 to administer the abstinence ‘pledge' upon the gathered masses. Couple this with the fact that previously a well-known ‘second apostle' of this movement, Rev. John Foley, who was a Catholic Curate in Youghal but hailed from Clashmore itself, had already exerted his considerable influence on the ‘unemancipated' masses of Clashmore village itself and the surrounding areas in an attempt to free them from the scourge of the ‘grain'.

Back to Articles

|

River several hundred metres upstream just south of O'Riordan's farm buildings as they are today. In all, this ‘watercourse' had a substantial fall of 14 feet and eventually crossed the road under a shallow bridge at what was the old forge at the time. It then ran due south along the back wall of the mill buildings where it fed the worm tub and coppers which needed a constant supply of cold water and at one point drove two metal water wheels which presumably served both enterprises i.e. the internal machinery of the distillery such as the pumps and the millstones within the flour mill. It is a testament to the fall of water here if it was utilized to supply both the distillery and flour mill adjacent to each other, but it is not clear if both operations ran in parallel during this period. The distillery chimney itself presumably served the furnaces which heated the stills but also possibly doubled as a mechanism for drying the malted barley which was employed within some distilleries. Distribution of the finished product was relatively straight-forward for the distillery as the casks merely had to be transported by horse and dray to nearby Raheen Quay where they would be loaded on to a waiting ‘lighter' by the ‘lightermen' (a lighter was a type of barge for carrying goods) and brought to the nearby port of Youghal for shipping. In return the lighters would bring in much of the raw barley product for use in the distillery, along with coal, timber and many other supplies for the retailers of the village.

River several hundred metres upstream just south of O'Riordan's farm buildings as they are today. In all, this ‘watercourse' had a substantial fall of 14 feet and eventually crossed the road under a shallow bridge at what was the old forge at the time. It then ran due south along the back wall of the mill buildings where it fed the worm tub and coppers which needed a constant supply of cold water and at one point drove two metal water wheels which presumably served both enterprises i.e. the internal machinery of the distillery such as the pumps and the millstones within the flour mill. It is a testament to the fall of water here if it was utilized to supply both the distillery and flour mill adjacent to each other, but it is not clear if both operations ran in parallel during this period. The distillery chimney itself presumably served the furnaces which heated the stills but also possibly doubled as a mechanism for drying the malted barley which was employed within some distilleries. Distribution of the finished product was relatively straight-forward for the distillery as the casks merely had to be transported by horse and dray to nearby Raheen Quay where they would be loaded on to a waiting ‘lighter' by the ‘lightermen' (a lighter was a type of barge for carrying goods) and brought to the nearby port of Youghal for shipping. In return the lighters would bring in much of the raw barley product for use in the distillery, along with coal, timber and many other supplies for the retailers of the village. industry and the income of barley growers, especially in Cork and neighbouring counties where the ‘total abstinence' movement was centered. In the decade following the start of the temperance campaign in 1838, the number of bushels of malt upon which the required duty was paid fell by about 25% and crucially in the same period the consumption of grain spirits in Ireland had declined by about 50% which likely had a detrimental effect on the industry locally. There is strong evidence of the influence of the ‘temperance movement' in Clashmore and West Waterford in general and indeed Fr Mathew visited the village himself in 1842 to administer the abstinence ‘pledge' upon the gathered masses. Couple this with the fact that previously a well-known ‘second apostle' of this movement, Rev. John Foley, who was a Catholic Curate in Youghal but hailed from Clashmore itself, had already exerted his considerable influence on the ‘unemancipated' masses of Clashmore village itself and the surrounding areas in an attempt to free them from the scourge of the ‘grain'.

industry and the income of barley growers, especially in Cork and neighbouring counties where the ‘total abstinence' movement was centered. In the decade following the start of the temperance campaign in 1838, the number of bushels of malt upon which the required duty was paid fell by about 25% and crucially in the same period the consumption of grain spirits in Ireland had declined by about 50% which likely had a detrimental effect on the industry locally. There is strong evidence of the influence of the ‘temperance movement' in Clashmore and West Waterford in general and indeed Fr Mathew visited the village himself in 1842 to administer the abstinence ‘pledge' upon the gathered masses. Couple this with the fact that previously a well-known ‘second apostle' of this movement, Rev. John Foley, who was a Catholic Curate in Youghal but hailed from Clashmore itself, had already exerted his considerable influence on the ‘unemancipated' masses of Clashmore village itself and the surrounding areas in an attempt to free them from the scourge of the ‘grain'.